This week, I'm taking a closer look at Colombia's endangered rainforest trees and how they end up on luxury patios in the U.S. (and how that trade funds armed groups while forcing Afro-Colombian and Indigenous workers into heavy, unpaid labor). Then I head to Equatorial Guinea, where one of the men behind a failed British-led coup (yes, really) just died---and remind myself how often Western elites quietly fund chaos worldwide for oil and power.

Plus, a Tuareg legend passed away, an art exhibition on textile art in Tunisia, a new Egyptian series about child abuse, a documentary on Shireen Abu Akleh, and a smart approach to malaria in Djibouti.

Chocó rainforest trees are going extinct --- but they're all over US patios

What happened:

A new report from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) shows that timber illegally cut from Colombia's Chocó rainforest is being sold in the US, Canada, and Europe. Over four years, the EIA used hidden cameras, satellite images, and public records to investigate the trade. What they found: trees are being cut without permits, sold with fake papers, and the money is funding armed groups.

Why this matters:

The Chocó rainforest runs along Colombia's Pacific coast and is one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth. It's packed with plants and animals that exist nowhere else; like the Amazon, but smaller (about the size of Ireland). It's also one of the rainiest places in the world. Illegal logging is destroying it.

Tell me more:

From 2020 to 2023, Colombia exported over US$24 million worth of timber that had no official documents proving it was legally cut or showing where it came from, from two regions---Chocó and Antioquia. That's about 30,000 trees, or the size of 70 square miles of forest (about the size of Washington, D.C.). 17 U.S. companies alone imported over US$4 million of this wood; most of the shipments had no valid documents showing the species, origin, or legal status of the wood.

How does the timber industry work?

Let's break it down. There are two types of timber trade: legal and illegal.

In the legal trade, every log of wood needs paperwork that says exactly what kind of tree it is, where it was cut, and proof that the logging was approved by the authorities. Think of it like a passport for wood. This is supposed to make sure the logging didn't harm protected forests or involve any crimes.

In Colombia, these papers are handled by local agencies, not one central national office. And those local offices often don't have the resources or independence to do their job properly (they're easily manipulated; hello corruption). That's where the system breaks down. Cue "illegal trade".

In the illegal trade, loggers cut down trees without permission, often in "protected areas". Then they use fake papers, or they "launder" the wood using real papers from another legal logging site. That way, it looks clean---but it's not.

Most of this illegal logging happens near rivers because it's easier to move the wood by water. Logs are floated downstream or dragged by animals. There are no checkpoints and no inspections. Armed groups like the Urabeños and Águilas Negras control access to the regions and charge bribes---sometimes thousands of U.S. dollars---to allow shipments to pass.

What is the illegal timber trade doing to the forest?

I'll give you two very concrete examples.

- Cumarú logging Ever heard of Cumarú? Cumarú is one of the most prized tropical hardwoods, and it is used in luxury patios and outdoor furniture (it's extremely sturdy and lasts decades). However, Cumarú trees are being logged so heavily, they're nearing extinction.

- Riverbank erosion There's also the riverbanks that are eroding. As I mentioned, most of the illegal logging happens to the trees on these said riverbanks (they're easier to access by boat). But those trees do more than just stand there---they hold the soil in place. Cut them down, and the soil slips into the water. That causes erosion, dirties the river, and harms fish and other wildlife.

What is it doing to the people?

The people cutting down these trees are mostly African-Colombian or Indigenous. Armed groups force them to work in 40°C (104°F) heat, using unsafe tools. Injuries are common---some even lose limbs. Many workers aren't paid real wages. Instead, they're given food, alcohol, or tools as payment. Some do receive small amounts of money, but by the time they cover the costs of chainsaws, fuel, and river transport---often charged to them by the same people employing them---they're left with nothing. One logger said: "The day you get paid, you can't even buy a candy for your kid." These conditions are so exploitative that some describe it as a form of modern slavery.

What now?

Tbd. Colombia's environmental ombudsman is investigating. A US-Colombia watchdog team---part of their free trade deal---is also reviewing the case. In general, the more awareness this specific part of Colombia gets, the better.

Plus, don't blame this all on Colombia. Importers are also to blame. Under the US Lacey Act and EU laws, companies must prove timber is legal. Many don't. As EIA's Susanne Breitkopf put it: "Importers are failing to ask the right questions---and hiding behind ignorance. That's not an excuse."

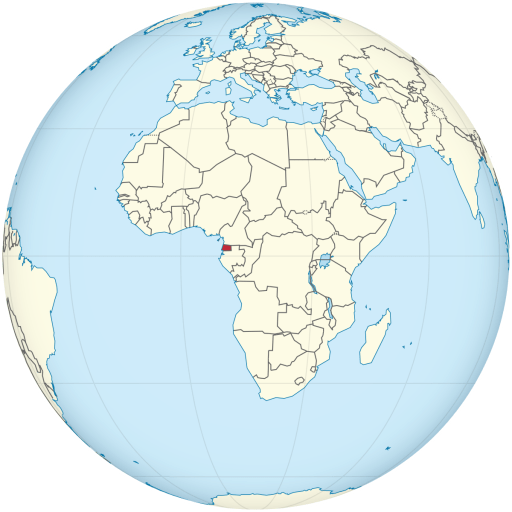

One of the main men behind the "wonga coup" in Equatorial Guinea died last week

What happened:

Simon Mann, British, ex-SAS, Eton graduate, died at 72 last week. He's known for leading a failed coup in 2004 to overthrow Teodoro Obiang, the president of Equatorial Guinea, a small country in West Africa with massive oil and gas reserves. The operation was called the "wonga coup" (because the goal was money, and "wonga" is British slang for cash).

Why this matters:

This is a clear example of neo-colonialism: powerful people from wealthy countries attempting to control the politics and resources of a poorer nation without taking official power. The goal was never democracy; it was oil money. And it shows how Western elites can help plan international crimes and still walk away with fines or pardons.

Tell me more:

Mann and about 70 mercenaries, mostly former South African soldiers, were arrested in Zimbabwe while flying in a plane full of weapons (yes, really) on their way to Equatorial Guinea. The goal? To overthrow Obiang and replace him with Severo Moto, an opposition figure living in exile. However, Zimbabwean authorities stopped the plane in Harare, and then-President Robert Mugabe had them jailed. Later, Mann was extradited to Equatorial Guinea, tried in court, and sentenced to 34 years. He served just over five years before Obiang pardoned him. He returned to the UK, married three times, a couple of children, mostly a quiet life. Mann died while exercising at the gym.

Who supported them and why?

- Mann wrote from prison that the coup had financial backing from international elites and that at least three governments may have known, including Spain (which colonized Equatorial Guinea).

- He named Mark Thatcher, son of former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and said that Thatcher helped fund the plan---specifically, a helicopter for Moto's escape. Thatcher denied knowing it was a coup, but admitted funding part of the operation and got a suspended sentence in South Africa.

- The widely accepted motive---to gain access to Equatorial Guinea's oil and gas---is supported by a lot of investigative journalists and leaked documents. It's not legally proven, but the connections are strong.

"Fun" facts:

When the coup was exposed,...

Please log in or subscribe for free to continue reading this issue.

We could use your help to make this issue better. Take a look at the requests below and consider contributing:

- Submit a piece of artwork for this issue

- Submit a news, academic or other type of link to offer additional context to this issue

- Suggest a related topic or source for future issues

- Fix a typo, grammatical mistake or inaccuracy

Below you'll find some of the sources used for this issue. Only sources that support "media embedding" are included.

-

Satirist John Fortune has been signed up by the BBC to develop a drama based on the aborted coup in Equatorial Guinea allegedly involving Mark Thatcher. By Jason Deans.

-

El cubanoamericano Mario Echevarría pedía una indemnización a la agencia turística por reservar hoteles en una propiedad confiscada en Cayo Coco

-

Sudan has vowed “to knock on every judicial door,” after the International Court of Justice...

-

“Está ya demandado y hubo una primera resolución, ahora estamos esperando”, aseguró la presidenta de México en conferencia.

-

Bringing Taiwan to the World and the World to Taiwan

-

In a world riddled with identity crises, cultural tensions and ecological urgencies, Hamid Zénati’s work reminds us that it is possible to re-member what has been dismembered, to forge new connections. Through colour. Through slowness. Through care.

-

Zeteo uncovers the hidden identity – and fate – of the Israeli soldier who killed the famous Palestinian-American journalist in 2022.

-

Visit Shahid.net or download the app now to watch the 1st season of Lam Shamsiyya and all the latest episodes in HD.

Each week, What Happened Last Week curates news and perspectives from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The newsletter is written by Sham Jaff and focuses on stories that rarely receive sustained attention in Western media.

Read the free edition every week. VIP subscribers receive additional stories, recommendations on what to watch, read and listen, and more.