This week, I'm looking at the ongoing fighting in the DRC---what's happening now, what Rwanda has to do with it. A decade after Assad gassed civilians in their sleep, survivors are speaking out, but justice is nowhere in sight, while chemical weapons quietly stick around. Antibiotic resistance is turning small cuts into deadly threats, especially for kids in places like Zimbabwe and Puerto Rico. Plus: Modi made a big power grab in India's capital, Sudan's military is closing in on Khartoum (thanks, Iran?), and two political giants--- Namibia's Sam Nujoma and the Dalai Lama's brother---passed away. Also: Guinea wiped out sleeping sickness, a Kurdish online film fest is here, Afghan girls share their experiences with the ban on education, and a tiny Costa Rican supermarket just took down Nintendo.

In 2013, Syria's Assad gassed civilians in their sleep. Today, survivors can finally speak freely---but justice is nowhere in sight

What happened:

Shortly after midnight on August 21, 2013, the Syrian regime under Bashar al-Assad launched a chemical attack on Ghouta, near Damascus. The rockets were filled with sarin, a deadly nerve agent. By morning, at least 1,144 people were dead. Another 6,000 were left gasping for air, convulsing, and suffocating, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

Why this matters:

What happened in Ghouta on August 21, 2013, was the largest single chemical weapons attack since Halabja 1988. Chemical weapons are still a 21st-century problem. Ghouta wasn't the first attack. It wasn't the last. And for survivors, justice remains out of reach.

Tell me more:

This attack wasn't random. It was coldly calculated. SNHR investigators later found that the Syrian military deliberately launched the attack when the weather conditions ensured maximum lethality---cool, still air meant the sarin gas would linger near the ground instead of dispersing. It was designed to kill as many people as possible in their sleep.

Aren't chemical weapons illegal?

Yes, and that didn't stop Assad. After the attack, the Assad regime denied responsibility, blamed militant groups, and later agreed to destroy its chemical arsenal under the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). But Syria never fully disarmed. Between 2013 and 2023, the regime carried out 222 more chemical attacks, killing at least 1,514 people. Even after the OPCW declared Syria's stockpiles destroyed in 2014, Assad's forces continued using sarin and chlorine gas in rebel-held areas. "Approximately 98% of all these attacks have been carried out by Syrian regime forces, while approximately 2% were by [the Islamic State group]," the SNHR said.

Why Ghouta?

For years, eastern Ghouta was one of the most contentious front lines in the Syrian civil war. The area was under opposition control, and Assad's forces had been bombing and starving the population under siege for years. But in 2018, the regime finally retook Ghouta. After that, even speaking about the chemical attack was dangerous---Syrian security forces arrested and intimidated survivors into silence. That all changed in late 2024. By December, Assad had fled to Russia, and his regime collapsed.

What do survivors say?

💬 "That night, even the narrow streets were packed with bodies. It was impossible not to step over the dead. It felt like the start of the apocalypse." -- Mohammed Barakat Khalife

💬 "If I'd spoken out before, Bashar al-Assad's forces would have cut off my tongue." -- Umm Nabil, who lost 22 family members that night.

💬 "There wasn't a door in Zamalka that we opened without finding entire families dead. Most of them died while they were fast asleep." -- Mohammad Ahmed Suleiman, a paramedic whose father, brother, sister-in-law, and their two children all suffocated in the attack.

💬 "Assad is gone, but we want to see him on trial for what his bloodstained hands have done. Until then, our pain will not go away." -- Suleiman

Dig deeper:

Nicole Di Illio's "The Continuing Tragedy of Ghouta's Chemical Attacks" (New Lines Magazine)

What now?

There's consensus that Syria's chemical arsenal was never fully eliminated. Hundreds of tons of chemical weapons remain unaccounted for, including 360 metric tons of sulfur mustard and nerve agent precursors. Plus, the fall of Assad means these weapons are unsecured---potentially up for grabs by ISIS or other armed groups. The new Syrian government, led by Ahmed al-Sharaa (HTS leader-turned-ruler), says it will cooperate with the OPCW---but trust in his regime is thin. And as for accountability: Assad himself is untouchable in Russia, but his former military officials and scientists could still face prosecution if there's a push for war crimes trials against them.

Zoom out:

Chemical weapons haven't gone away---they're just harder to track and confirm. Governments and armed groups continue to find ways to use them, despite global bans. For example,

- "Sudan's Military Has Used Chemical Weapons Twice, U.S. Officials Say" by Declan Walsh & Julian E. Barnes for New York Times

- "Russia used chemical weapons 434 times in December, Ukraine's General Staff says" by Abbey Fenbert for The Kyiv Independent

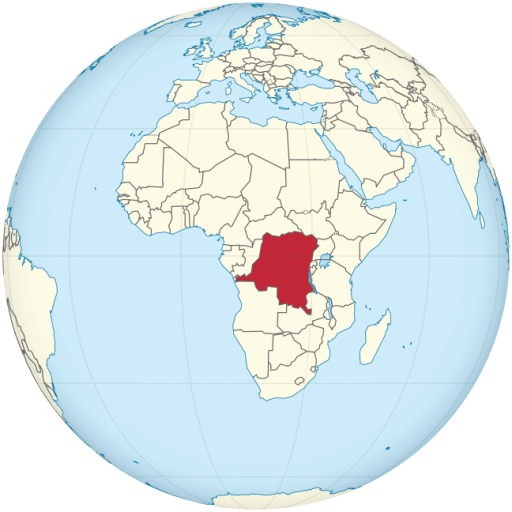

What's the fighting in DR Congo all about?

What happened:

Last week, in just a few days, fighters from the armed group M23 took control of nearly all of Goma, a major city of over a million people. And just as suddenly, on Monday, the M23 fighters and their allies announced a "humanitarian ceasefire", and resumed fighting again, this time in Kavumu. The situation's highly volatile. Take this explainer as a momentary screenshot.

Why this matters:

According to the United Nations, at least 2,700 people have reportedly died since. Independent observers say the number could be much higher. Plus, there's a report by The Guardian about a mass jailbreak in Goma, where M23 rebels raped and burned alive hundreds of women. The UN confirmed the attack, but can't fully investigate because the group is blocking access.

Wait, who's fighting who?

- The M23 rebels---a group of mostly ethnic Tutsi fighters who claim they took up arms to protect their minority rights. They named themselves after a failed 2009 peace deal (March 23, hence M23). According to the UN, DR Congo and France, the M23 are backed by Rwanda. Rwanda denies it, but many reports say Rwandan troops are fighting alongside M23.

On the other side:

- The Congolese military, which has been bombing M23 positions with aircraft.

- The Southern African Development Community (SADC) military force, which recently joined the fight but has struggled to hold back M23.

- UN's peacekeeping mission in DR Congo (MONUSCO), which has fired artillery to support Congolese troops.

Why Goma and why now? - Because Goma.. ...isn't just any city. It's right on the border with Rwanda and sits next to Lake Kivu, making it a crucial trade and transport hub. But more importantly, it's surrounded by mining towns producing gold, tin, and coltan---aka the minerals powering your phone, laptop, and every other gadget you rely on.

- Because now... The time might have been "right", say some analysts---new U.S. leadership, new African Union leadership, and a shifting geopolitical landscape.

What's Rwanda got to do with this?

This all goes back to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. The tension that fuels this war isn't new---it's been boiling for decades.

- 1994: Hutu extremists (also called the Interahamwe and Rwandan government forces) massacred 800,000 Tutsis in Rwanda in 100 days.

- After the genocide: A Tutsi-led armed force under Paul Kagame (now Rwanda's president) overthrew the Hutu-led government and defeated the extremists. Hutu fighters fled into eastern DR Congo, setting off years of war. Rwanda invaded DR Congo twice, claiming it was hunting down genocide perpetrators.

- Today, Hutu armed groups (like the FDLR) still operate in eastern DR Congo. The FDLR is an armed group who massacred Tutsis during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and Rwanda sees them as a direct security threat---accusing Congo of sheltering them. DR Congo denies this.

And DR Congo's mineral wealth?

And most likely, this is about money, too. M23 has seized mining areas rich in gold, tin, and coltan. A UN report in December found that 120 tonnes of coltan were being smuggled into Rwanda every four weeks. Rwanda's mineral exports have mysteriously increased---with most of that believed to be stolen from DR Congo. Rwanda, as expected, denies any involvement.

Dig deeper:

The "international community" has been slow to take action, like imposing sanctions against Rwanda. One big reason for this is the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Countries like the US, UK, and Belgium, didn't intervene to stop the killings, and some feel guilty about that failure. France is especially criticized for its role in enabling the genocide. Because of this sensitive history, Western countries are hesitant to hold Rwanda accountable for its actions in Congo, despite the growing criticism of Kagame's government, writes Arne Schütte for Table.Media.

What now?

African leaders (8 countries of the East African Community and 16 from the Southern African Development Community) met in Tanzania on Friday (February 8), to address the situation, reports DW. Tanzania's president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, made it clear: if the leaders don't act, they'll be judged harshly by history. The summit called for an immediate ceasefire and peace talks, but getting everyone on the same...

Please log in or subscribe for free to continue reading this issue.

We could use your help to make this issue better. Take a look at the requests below and consider contributing:

- Submit a piece of artwork for this issue

- Submit a news, academic or other type of link to offer additional context to this issue

- Suggest a related topic or source for future issues

- Fix a typo, grammatical mistake or inaccuracy

Below you'll find some of the sources used for this issue. Only sources that support "media embedding" are included.

-

How to get the country’s new rulers to help eliminate Assad’s deadly arsenal.

-

These included K-51 and RG-VO munitions, anti-riot weapons that are prohibited for use in warfare, and ammunition loaded with chemicals of "unspecified type."

-

Crisis in DRC: UN peacekeepers protecting civilians - and themselves - from large-scale offensive operations by M23 rebels | United Nations PeacekeepingThis story was written by Lesley Myers, Editor for UN peacekeeping’s Strategic Communications team. Lesley is a political analyst and strategic planner with over 15 years’ experience in data-driven politics, development, and peacekeeping. The resumption of hostilities in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is taking a devastating toll on civilians and risks a

-

Obwohl der internationalen Gemeinschaft klar ist, dass Ruandas Präsident Paul Kagame hinter der Eskalation im Ostkongo steckt, gibt es bisher keine Sanktionen gegen Kigali. Denn das Land hat im Westen bisher ein gutes Ansehen. Das hat viele Gründe – historische, politische und wirtschaftliche.

-

African leaders asked defense chiefs for a road map to end the conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Their emergency talks in Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea come as the long-running crisis escalates.

-

Scientists and doctors can't keep up with the tidal wave of people whose bodies don't respond to basic antimicrobial treatment.

-

Libya authorities uncovered nearly 50 bodies this week from two mass graves in the country’s southeastern desert in the latest tragedy involving people seeking to reach Europe through the chaos-stricken North African country.

-

Pictures and videos show the intensely coloured water flowing into an estuary, the Rio de la Plata.

-

Monitor warnings and predicted arrival times for the ocean wave.

-

Ten houses were buried and hundreds were forced to evacuate after the landslide in southwest China on Saturday.

-

Navi Pillay, head of U.N. Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, also said she would support a charge of apartheid against Israel at the ICC.

-

The Bodleian Libraries and the Vesuvius Challenge have announced a historic breakthrough in the endeavour to decipher text preserved on papyrus scrolls from the ancient site of Herculaneum. Researchers have successfully generated the first image of the inside of scroll PHerc. 172, one of three Herculaneum scrolls housed at the Bodleian Libraries, which was buried by the

-

As Trump returns to office, the question is whether change will come at the negotiating table or on the battlefield.

-

A small supermarket in Costa Rica named "Super Mario" has successfully defended its trademark against video game giant Nintendo.

Each week, What Happened Last Week curates news and perspectives from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The newsletter is written by Sham Jaff and focuses on stories that rarely receive sustained attention in Western media.

Read the free edition every week. VIP subscribers receive additional stories, recommendations on what to watch, read and listen, and more.